NYSOH Saw Record Enrollments Even Before the Pandemic Started

More New Yorkers than ever turned to NYSOH for affordable health coverage at the beginning of 2020. The latest NY State of Health (NYSOH) report shows that 25 percent of New Yorkers (4.9 million) enrolled in health coverage through the NY State of Health during 2020’s Open Enrollment Period.[1] This represents a 150,000 increase over 2019. The report documents enrollment between November 1, 2019 and February 7, 2020. Enrollment through NYSOH has increased every year since it was created, an indication of the need New Yorkers have for health coverage.

Most New Yorkers who used NYSOH enrolled in public plans like Medicaid (3.4 million), Child Health Plus (452,000), and the Essential Plan (797,000). Medicaid and the Essential Plan cover New Yorkers who earn up to 250 percent of the federal poverty level. Child Health Plus covers New Yorkers under the age of 19 with subsidies for families at lower incomes. About 273,000 New Yorkers used NYSOH to purchase private health insurance (Qualified Health Plans or QHPs), 60 percent with financial assistance through premium subsidies. QHP enrollees continued to show a preference for lower-cost options, with Bronze and Silver plans (plans with lower premiums) being the most popular throughout the State. Increasing premium costs are likely the cause of this trend towards lower premium plans, but those lower premiums come with higher deductibles. Even insured New Yorkers report struggling to afford health care – the trend towards enrollment in plans with lower premiums but higher cost-sharing is an important one for advocates to monitor.[2]

Assistors continued to play a key role in the success of last year’s Open Enrollment period, with around 80 percent of last year’s enrollments being conducted by assistors. Navigators, who are trained and certified by the state, are available to provide assistance all across New York – you can find help in your own community by calling 888-614-5400.

NYSOH has proven itself resilient over the years, from the early days when it was unclear whether or not consumers would use it at all through the Trump era when federal policy changes hurt Marketplaces in other states. In the months after this report covers, NYSOH took steps to ensure that New Yorkers were able to keep enrolling in health coverage even as millions lost their jobs or experienced other disruptions during the pandemic. Preliminary data shows that between February 2020 and February 2021, an additional 885,000 New Yorkers used NYSOH to obtain health insurance, and now a record 5.8 million people are enrolled through NYSOH—nearly a third of the state’s entire population.[3] This was only possible because of the investments New York has made over the years towards building a strong, integrated Marketplace where consumers have lots of help available to make the best choices for themselves.

[1] NY State of Health At A Glance 2020 Open Enrollment Report

[2] New Statewide Healthcare Affordability Survey | Community Service Society of New York (cssny.org)

[3] NYSOH Press Release: NY State of Health Announces Enrollment Surges, More than 5.8 Million New Yorkers Enrolled in Health Coverage

Across the United States, communities are struggling to overcome a global pandemic. And at the same time, Black, Indigenous, and peoples of color are once again disproportionately impacted due to systemic racism. In addition to overcoming the numerous inequities that have long been ignored, in the time of COVID-19, Asian Americans — particularly those who are East Asian-presenting — have seen an explosion of xenophobia and racial violence. Health Care For All New York (HCFANY) condemns this racial violence and urges our elected officials to enact policies that advance health equity. HCFANY is a statewide coalition of 170 consumer-focused organizations dedicated to achieving quality, affordable health coverage for all New Yorkers, and ensuring that the concerns of real New Yorkers are heard and reflected in policy conversations.

According to Stop AAPI Hate, a joint initiative that has been tracking Coronavirus-related incidents of harassment, hate speech, and/or violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, there were 3,795 reported incidents in the US from March 19, 2020 to February 28, 2021. Over 500 of these incidents (14%) took place in New York. NYPD data shows there were at least six attacks on Asian Americans in January and February 2021, compared to none during those months in 2020. Additionally, many bias-based incidents continue to go unreported.

Hate crimes themselves perpetuate health equity issues. Discrimination-related stress has been shown to result in health disparities, and victims of hate crimes suffer long-term effects like depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

There is a long history of racism and xenophobia against Asian Americans in the U.S., particularly during times of economic hardship, alleged threats to national security, and/or disease. And there is a long history of anti-Asian racism being enacted into law, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Underlying these policies are racist and harmful stereotypes of Asians as a “model minority,” pitting communities of color against each other and rendering those who struggle invisible; or Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners and un-American in their own communities. The COVID-related hate incidents of today, fueled by racist statements and misplaced anger towards those perceived as Chinese, perpetuate this history.

Inequities faced by Asian Americans and other communities of color have also been demonstrated through the inadequacy of COVID-19 data reporting and subsequent public health response efforts. Data collection and reporting on race and ethnicity can be vastly different across state, county, and local health systems. For example, Asians are sometimes classified as “Other” and/or aggregated with other racial groups due to their smaller population size. And even when Asian American population data is collected and reported, failure to disaggregate the data by Asian ethnicity erases the variations in economic, social, and cultural diversity among Asian subgroups.

These differences have an effect on whether certain Asian populations, especially immigrants, are likely to have health insurance coverage, whether they may be at increased risk of certain chronic conditions or diseases, and what interventions may be more successful. It is impossible to address these issues without access to data that accurately defines the problem.

Immigrant communities also face barriers to COVID-19 testing, care, and vaccination because of the lack of language access and cultural relevance of accurate information on prevention, testing, and vaccines. Additionally, anti-immigrant attacks, from hate crimes to Trump-era attempts to curtail immigrant access to care, intensify fears and create barriers to care for members of multi-generational households, especially those with mixed immigration status.

To advance health equity, we must come together to fight for racial justice. We need to hold policy makers at all levels of government to be accountable to the needs of communities that are most impacted by systemic racism, and also be committed to creating systemic changes to ensure equitable access to healthcare. HCFANY applauds the State’s commitment to providing $13 Million to support Asian American community-based organizations and to support implementation of data disaggregation of diverse Asian ethnic groups. HCFANY urges state and local leaders to: (1) work in partnership with the Coalition for Asian American Children and Families (CACF) and partnering Asian American community organizations in implementing the robust collection, monitoring, and reporting of disaggregated health data; (2) expand affordable Essential Plan coverage to all New Yorkers, regardless of immigration status; (3) support safety net hospitals that treat diverse New Yorkers of all race, ethnic, national origin, and language backgrounds; and (4) ensure equity and access (especially language access) to COVID-19 information, testing, treatment, and vaccines through community-based measures like pop-up vaccine sites with appropriate in-person interpretation and translation in hard-to-reach AAPI and other underserved communities.

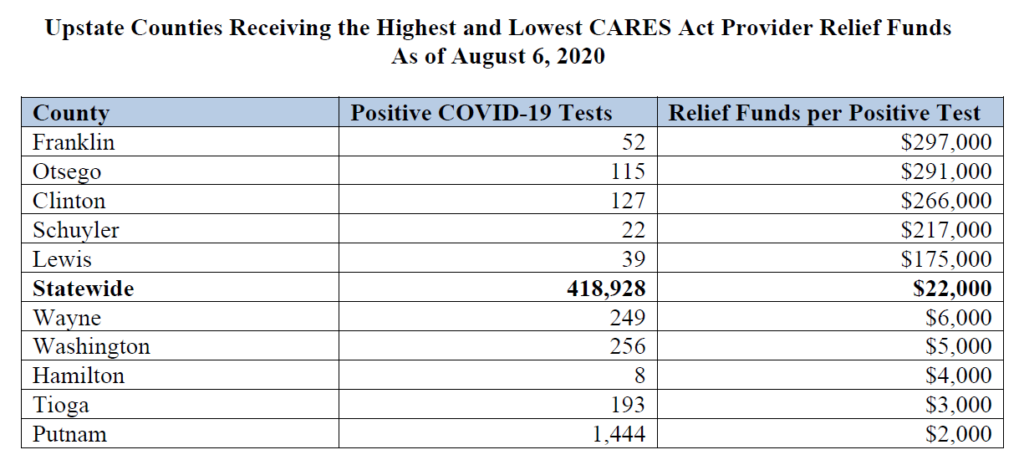

The Provider Relief Fund created by the Coronoavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act is the biggest source of support for healthcare providers caring for COVID-19 patients. Yet, CARES Act disbursements vary enormously across New York, with little relationship to COVID-19’s burden. Providers in Putnam County, which has had around 1,400 confirmed COVID-19 cases, received the lowest funding: just $1,950 for each confirmed case. Franklin County, which received the highest funding, received $297,000 for each of its 52 confirmed cases. That’s 150 times higher! (Data on provider relief payments can be found here, and data on the number of COVID-19 cases by county here.)

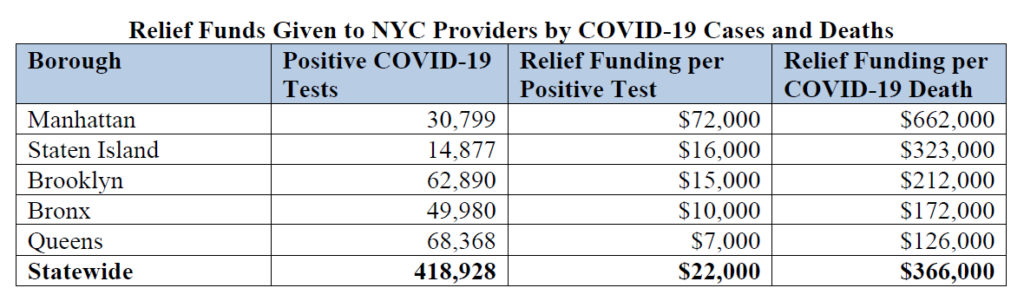

The funding disparity also exists within New York City. Providers in Manhattan received over ten times as much relief funding as those in Queens compared by the number of confirmed cases.

Sources: New York State Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control.

Many of the positive cases identified outside of Manhattan may have resulted in care provided in Manhattan. Yet there is still a huge disparity when comparing the funding by the number of fatalities occurring in each borough, which would reflect differences in the burden experienced by providers. For every patient that died in Queens, providers there received about $126,000 in relief. In Manhattan, providers received $662,000 for every patient that died.

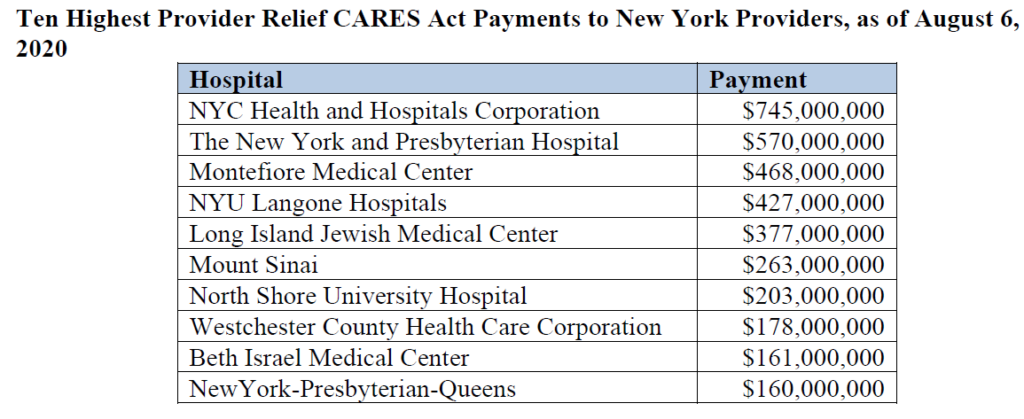

Troubling variation can also be seen at the provider level. The biggest payment, $745 million, went to the NYC Health and Hospitals Corporation. However, that system includes 11 different hospitals – which means it received just about $68 million for each facility. Other hospitals in the top ten appear to be individual facilities, and all received far more than $68 million. New York Presbyterian appears twice – it received $570 million for one of its hospitals in Manhattan and another $160 million for its hospital in Queens. Montefiore Medical Center received $468 million plus additional payments for its hospitals in New Rochelle and Mount Vernon.

Why has this happened?

Provider Relief funding is also meant to replace lost revenue so healthcare providers unable to see patients can stay open, and to cover the costs of testing and treatment for uninsured Americans. But it is still concerning that there is so little relationship between the impact COVID-19 had in different parts of the state and the amount of relief providers received.

The first Provider Relief disbursements were based on hospitals’ patient revenue – which guaranteed that safety-net providers (whose payer mix includes more uninsured patients and more patients covered by Medicaid) received far less funding. Later disbursements attempted to address the initial maldistribution. High Impact payments were distributed based on a threshold of COVID-19 admissions, meant to ensure at least $50,000 for every eligible admission. Another targeted disbursement went to hospitals with low profit margins or surpluses, uncompensated care costs of at least $25,000 per bed, and a Medicare Disproportionate Patient Percentage of at least 20.2 percent. However these additional targeted disbursements clearly fell short.

Federal funding disparities are just one of the reasons safety-net hospitals are under resourced. State policies such as the indigent care pool disbursements and our failure to reach universal health coverage also play a big role. Future relief packages must do something to get relief funding to providers caring for the highest number of COVID-19 patients.