Every September, healthcare providers see a rise in asthma-related hospitalizations. The third week of September is known as Asthma Peak Week; ragweed levels—a common fall pollen allergy—are peaking, mold counts are increasing as leaves start to fall, children are catching respiratory infections as they go back to school, and flu season is just beginning. Proper asthma control is essential to stay healthy and manage symptoms during this month. However, for many, healthcare costs are making it difficult to manage or control their symptoms.

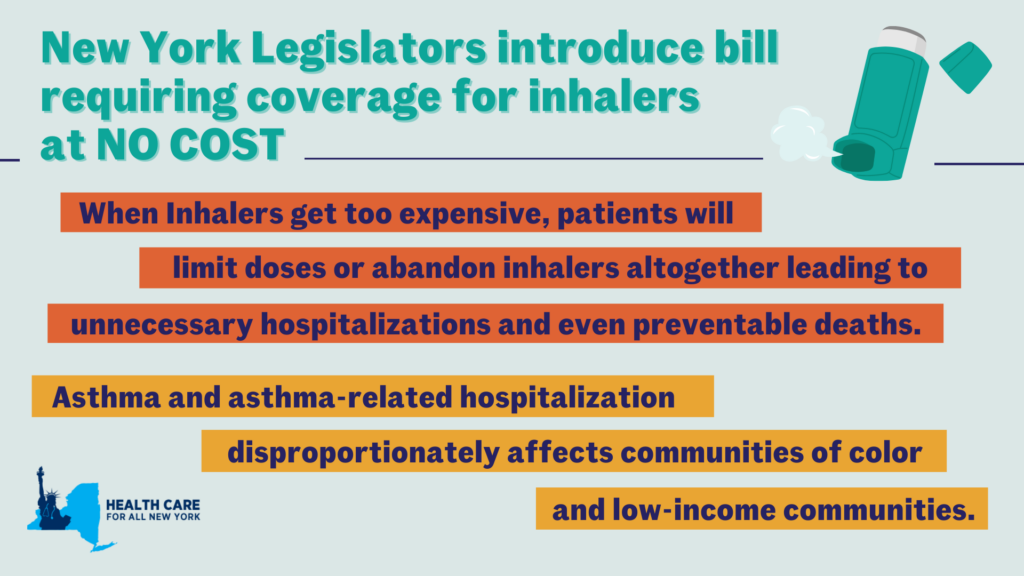

In New York, asthma impacts more than 1.4 million adults and an estimated 315,000 children, according to the New York State Department of Health and the US Center for Disease Control, respectively as of 2021. The price of asthma inhalers, a lifesaving and sustaining device, has drastically increased over the past decade and can cost an individual up to $645 a month, according to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP). At these high prices, some patients are rationing doses or even abandoning their inhalers—which can lead to unnecessary hospitalizations and even preventable deaths. Though with insurance, patients share the cost of an inhaler with their insurance provider through a deductible or copayment—even those with health coverage struggle to afford inhalers.

Asthma rates and asthma-related complications disproportionately affect communities of color and low-income communities in New York. Black New Yorkers are over nine times more likely to visit the Emergency Department (ED) for asthma-related complications than their White counterparts—four times more likely for Hispanic New Yorkers. Asthma-related ED visits are also three times as frequent for individuals in low-income zip codes when compared to those in higher-income zip codes. Asthma is an apparent public health issue affecting those already facing economic and environmental disparities.

Earlier this year, with pressure from the HELP committee and Senator Bernie Sanders, three of the largest producers of inhalers—AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline—agreed to cap their inhaler products, for both asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, at $35 or less per month. This price cap will be available for those on commercial insurance and those uninsured, which will be automatically applied at local pharmacies or accessed with a copay card. However, those enrolled in government insurance programs, like Medicare or Medicaid, are left behind due to federal restrictions.

Luckily, New York legislators, Assembly Member Jessica González-Rojas and State Senator Gustavo Rivera, have proposed a bill to remove this financial barrier by eliminating deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, or other cost-sharing requirements for inhalers and require insurance coverage for inhalers at no cost. González-Rojas introduced this legislation because of its significance to her district, representing communities in Queens, that have high rates of hospitalization due to asthma. Rivera represents the northwest Bronx, a borough with substantially higher asthma mortality rates than other New York City boroughs. We commend both González-Rojas and Rivera for taking these necessary actions in trying to address New York’s asthma crisis.

Minnesota and Illinois, Washington, and New Jersey have passed similar legislation that caps the cost-sharing requirements of inhalers at $25, $35, and $50 per month, respectively. We need New York to step up to the plate to save lives and treat asthma. “This smart bill will ensure that insurance cost-sharing is never a barrier to accessing life-sustaining inhalers for those who need it,” said Elisabeth R. Benjamin, Vice President of Health Initiatives at the Community Service Society of New York.

Guest Post by Melissa Genadri, Health and Economic Mobility Policy Associate, Children’s Defense Fund – New York

During the 2022 Midterm Elections, New York City voters overwhelmingly voted in support of a trio of ballot proposals focused on promoting citywide racial justice and ending systemic racism in City government. Spearheaded by the New York City Racial Justice Commission, a charter revision commission formed by former Mayor Bill de Blasio in 2021 to combat structural racism within New York City and chaired by FPWA CEO and Executive Director Jennifer Jones Austin, the proposals aim to center racial equity in City government decision-making – and also set a strong precedent for action that can be taken at the State level to create a more equitable New York for our children, young people, and families and, in particular, our communities of color.

By voting in favor of three racial justice ballot measures, New Yorkers approved several changes to the New York City Charter, the City’s Constitution. These measures were convincingly backed by New York City voters with wide margins, with each proposal receiving at least 70 percent of voter support. The first ballot measure, Add a Statement of Values to Guide Government, will add a preamble to the City Charter intended to guide City government in fulfilling its duties. The preamble will consist of a statement of foundational values and a vision aspiring towards “a just and equitable city for all” New Yorkers in such areas as housing, education, health care, economic mobility, and child and youth supports. The statement will also include an Indigenous land acknowledgment and a vow that the City must strive to remedy “past and continuing harms and to reconstruct, revise, and reimagine our foundations, structures, institutions, and laws to promote justice and equity for all New Yorkers.”

The second ballot measure will amend the City Charter to Establish a Racial Equity Office, Plan, and Commission. This measure creates both a new City agency, the Office of Racial Equity, and a Commission on Racial Equity that will be appointed by City elected officials to lead a citywide racial equity planning process. Part of this process entails creating Racial Equity Plans every two years which stipulate intended strategies and goals to improve racial equity in New York City and to reduce or eliminate racial disparities.

The third ballot measure, Measure the True Cost of Living, requires the city to develop and annually measure, beginning in 2024, a new ‘true cost of living’ metric which tracks the actual cost of meeting essential needs in New York City without consideration of public, private, or informal assistance and “is intended to focus on dignity rather than poverty.” The proposed measurement aims to shift the City away from the federal and local measures of poverty and will account for a wide range of expenses including costs associated with housing, childcare, transportation, healthcare, household items, and telephone and internet service.

The passage of the New York City racial justice ballot measures sets a strong precedent for our State to take urgent and decisive action to bolster racial justice and end systemic racial inequities. A critical way of doing so is through embedding racial impact analysis into our State’s legislative and rulemaking processes by no longer passing legislation or adopting rules without first examining whether or not these policies hold the potential to eliminate, perpetuate or create racial and ethnic disparities – and prohibiting the adoption of bills and rules that could increase such disparities. New York must thereby act swiftly to join the growing list of states who create racial and ethnic impact statements for proposed legislation and rules.

Furthermore, the overwhelming success of the racial justice ballot measures illustrates the importance of organizing and intentionally engaging community throughout the process of conceptualizing and refining racial equity policy. As detailed in their NYC for Racial Justice Final Report, the Racial Justice Commission conducted numerous one-on-one interviews with community-based organizations, held issue-specific panels with thought leaders, hosted virtual and in-person public input and listening sessions and solicited the submission of online comments as they worked to develop the ballot measures and gain community buy-in. The Commission also worked to spread word about the proposals to over 1,000 New Yorkers – with an emphasis on reaching communities of color – through presentations to community boards and civic groups and interviews and focus groups with racial justice stakeholders. Any statewide racial equity policy must similarly engage authentically and consistently with our communities to ensure that the policy is truly representative of the best interests of New York’s children, young people, families and communities of color.

There is clear and urgent need to take decisive action to end New York’s entrenched racial inequalities and promote equitable economic mobility. This is particularly evident with regards to the racial and ethnic disparities in New York’s alarmingly high poverty rates. As noted in a report released by New York State Comptroller DiNapoli last December, almost 2.7 million New Yorkers, or 13.9 percent of our State’s population, lived in poverty in 2021, compared to 12.8 percent of all Americans. Poverty rates are more than double for Hispanic New Yorkers compared to white, non-Hispanics, with one-fifth of New York’s Hispanic population living below the poverty level in 2021. Black, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander and American Indian New Yorkers experienced poverty at twice the rate of white New Yorkers in 2021. Racial and ethnic disparities are particularly pervasive in New York’s child poverty burden, with Black and Latinx children more than twice as likely as white children to live in poverty statewide and 10 to 13 times more likely than white children to live in poverty in Manhattan. The Child Poverty Reduction Act, which makes a public commitment to cutting child poverty in half in New York within ten years and establishes the Child Poverty Reduction Advisory Council (which CDF-NY was appointed to by Governor Hochul), represents a critical step towards reducing these jarring disparities. In addition to the tangible actions that can be taken through the Child Poverty Reduction Advisory Council, our State’s rulemaking and legislative processes must incorporate racial and ethnic impact analysis by codifying a racial and ethnic impact statement requirement. Undoing generations of racial and ethnic disparities and systemic harm demands an actively anti-racist approach that examines the role of legislative and regulatory action in perpetuating inequality in New York. It is past time to get it right.

Guest post by Medha Ghosh, Health Policy Coordinator, Coalition for Asian American Children and Families

On December 23, 2021, Governor Kathy Hochul signed the NYS Bill S6639/A6896 on Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (AA and NH/PI) data disaggregation into law.

This law mandates that all State agencies, departments, boards, and commissions that already collect demographic data must now collect data on the top ten most populous AA ethnic groups and specific NH/PI ethnic groups of New York State along with data on languages spoken. The law also specifies that such government entities must release such data to the public on an annual basis. This huge victory in the fight for better data for all was only made possible by over ten years of persistent advocacy by CACF and CACF’s members and partners!

Over the past two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the distinctive struggles faced by our AA and NH/PI communities in New York. While State and City public health data failed to show the disparities experienced by these communities, independent studies showed how Chinese Americans had the highest rates of COVID-related death and South Asian Americans the highest rates of COVID-related hospitalization in New York City. Disaggregated data will allow state officials and community organizations to better serve all communities through this ongoing public health emergency and beyond.

You can read more about the bill here and here.

Guest post by Lois Uttley, Women’s Health Program director at Community Catalyst and co-founder of Raising Women’s Voices for the Health Care We Need

When the first wave of COVID-19 hit New York City in the spring of 2020, it starkly revealed something health advocates had been worried about for some time. The neighborhoods when people of color were being hardest hit, such as in Queens and Brooklyn, were also the places where hospitals had closed or downsized in recent years, leaving inadequate capacity to meet the pandemic needs. The result was overcrowding, long lines and delays in evaluation and treatment.

A new law signed by Gov. Kathy Hochul in late December will help address this problem when hospitals and most other health facilities propose new changes, including reducing or eliminating services. Described as “landmark” legislation by its Assembly sponsor, Health Committee Chair Richard Gottfried, the Health Equity Assessment Act will for the first time require an independent assessment of the impact of such proposed changes on medically-underserved New Yorkers. The legislation (A191a/S1451a), sponsored in the Senate by Health Committee Chair Gustavo Rivera, was a top 2021 priority for Health Care for All New York and allies in the Community Voices for Health System Accountability (CVHSA) alliance.

The required independent health equity assessment would take place during preparation of a health facility’s Certificate of Need (CON) application to the New York State Department of Health seeking approval of a proposed transaction. Under the law, such an assessment must determine whether a proposed project would improve access to hospital services and health care, improve health equity and reduce health disparities within the facility’s service area for medically-underserved people. “Medically-undeserved” is defined in the law to include racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, women, LGBTQ+ people, people with disabilities, uninsured people and those with public insurance (such as Medicaid) as well as older adults, rural residents and people living with “a prevalent infectious disease or condition” (such as HIV).

Included in the assessment will be the extent to which the project would provide indigent care (both free and below cost), the availability of public or private transportation to the facility, the means of ensuring effective communication with non-English speaking patients, as well as those with speech, hearing or visual impairments and the extent to which the project would reduce architectural barriers for people with mobility impairments.

The health equity assessment must involve meaningful engagement of residents and leaders of affected communities, as well as public health experts, employees of the health facility and other stakeholders. HCFANY and CVHSA fought hard for the requirement that the health equity assessment must be posted on the NYS DOH website, as well as the health facility’s website, so that the community can read the assessment document and provide comments.

While the law does not require the disapproval of projects that don’t fare well in health equity assessments, it will certainly encourage health facilities to include provisions that address the needs of medically-underserved people, in order to secure state approval. Moreover, the assessments will provide valuable information for DOH officials and members of the Public Health and Health Planning Council, which approves major projects. They could potentially attach conditions to approvals of projects, in order to improve the health equity impact.

The effective date of the law, which was originally six months from signing, was extended out to 18 months by the Governor’s office, to allow for rulemaking by the NYS DOH and PHHPC. This means that HCFANY and CVHSA members will need to be actively involved in the rulemaking process, to ensure that the intent of the law is preserved in the implementing rules.